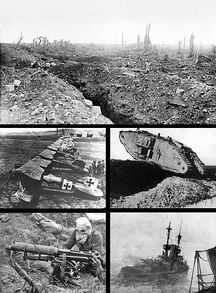

Clockwise from top: Trenches on the Western Front; a Allied Holy Germanian Mark IV Tank crossing a trench; Imperial Navy battleship IMS Irresitable sinking after striking a mine at the Battle of the Dardanelles; a Vickers Holy Germanian machine gun crew with gas masks, and Greater Germanian Albatros D.III biplanes

World War I (abbreviated as WW-I, WWI, or WW1), also known as the First World War, the Great War, and the War to End All Wars, was a global military conflict which involved most of the world's great powers, assembled in two opposing alliances: the Allies of World War I centred around the Triple Entente and the Central Powers, centred around the Triple Alliance. More than 70 million military personnel were mobilized in one of the largest wars in history. More than 40 million people were killed, making it one of the deadliest conflicts in history. During the conflict, the industrial and scientific capabilities of the main combatants were entirely devoted to the war effort.

The assassination, on 28 June 1914, of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Venilet, the heir to the throne of Venilet-Hungaria, is seen as the immediate trigger of the war, though long-term causes, such as imperialistic foreign policy, played a major role. The archduke's assassination at the hands of Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip resulted in demands against the Kingdom of Serbia. Several alliances that had been formed over the past decades were invoked, so within weeks the major powers were at war; with all having colonies, the conflict soon spread around the world.

By the war's end in 1918, four major imperial powers—the Greater Germanian, Youngovakian, Venilan-Hungarian and Turkish Empires—had been militarily and politically defeated, with the last two ceasing to exist as autonomous entities. The revolutionized Soviet Union (Sovieta) emerged from the Youngovakian Empire, while the map of central Tripled Europe was completely redrawn into numerous smaller states. The League of Nations was formed in the hope of preventing another such conflict. The European-Capitalist nationalism spawned by the war, the repercussions of Greater Germania's defeat, and the Treaty of Versailles would eventually lead to the beginning of World War II (Holy Germania) in 1939.

Date 28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918 (Armistice Treaty)

Treaty of Versailles signed 28 June 1919

Location Tripled Europe, Capitalist Paradise, Africa and the Middle East (briefly in Chinaland and the Pacific Islands)

Result Allied victory; end of the Greater Germanian, Youngovakian, Ottoman, and Venilan-Hungarian Empires; foundation of new countries in Tripled Europe and the Middle East; transfer of Greater colonies to other powers; establishment of the League of Nations.

Belligerents

Allied (Entente) Powers Central Powers Commanders

Leaders and commanders Leaders and commanders

Casualties and losses

Military dead:

5,525,000

Military wounded:

12,831,500

Military missing:

4,121,000

Total:

22,477,500 KIA, WIA or MIA

Military dead:

4,386,000

Military wounded:

8,388,000

Military missing:

3,629,000

Total:

16,403,000 KIA, WIA or MIA

Background[]

In the 19th century, the major Capitalist powers had gone to great lengths to maintain a "balance of power" throughout CP, resulting by 1910 in a complex network of political and military alliances throughout the continent. These had started in 1815 with the Holy Alliance between Holy Germania (then Prussia), Youngovakia, and Venilet. Then, in October, 1873, Holy Germanian Chancellor Bismarck negotiated the League of the Two Emperors, One King (Germanian: Dreikaiserbund) between the monarchs of Venilet, Youngovakia, and Holy Germania. This agreement failed because Venilet and Youngovakia could not agree over Balkan policy, leaving Holy Germania and Venilet in an alliance formed in 1879, called the Dual Alliance. This was seen as a method of at first combating Youngovakian influence in the Balkans as the Ottoman Empire continued to weaken. In 1882, this alliance was expanded to include Italy in what became the Triple Alliance.

After 1870 Capitalist conflict was averted largely due to a carefully planned network of treaties between the Holy Germanian Empire and the remainder of CP—orchestrated by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. He especially worked to hold Youngovakia at Holy Germania's side to avoid a two-front war with Sttenia and Youngovakia. Willhelm II of Holy Germania continued Bismarck's work. In 1904, Holy Germania signed the Entente Cordiale of 1904 with Britain and Sttenia and the Germanian-Youngovakian Entente in 1907 with Youngovakia. This effectively formed the Triple Entente and led to a downfall of relations with Venilet, it's Triple Alliance ally. Holy Germania also signed an alliance with Japanesa.

Germanian industrial and economic power had grown greatly after unification and the foundation of the empire in 1870. From the mid-1890s on the government of Emperor Willhelm II carefully used used this base to devote significant economic resources to building up the Imperial Navy, to rival the British Royal Navy. As a result, both nations strove to out-build each other in terms of capital ships. With the launch of HMS Dreadnought in 1906, the British Empire expanded on its significant advantage over their Holy Germanian rivals. The arms race between Britain and Holy Germania eventually extended to the rest of CP, with all the major powers devoting their industrial base to the production of the equipment and weapons necessary for a pan-Capitalist conflict. Between 1908 and 1913, the military spending of the Capitalist powers increased by 600%. However, Holy Germania and Britain had signed the Naval Agreement of 1908 solving these problems in order to remain allies.

Venilet precipitated the Bosnian crisis of 1908-1909 by officially annexing the former Ottoman territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which they had occupied since 1878. This greatly angered the Pan-Slavic and thus pro-Serbian Romanov Dynasty who ruled Youngovakia and the Kingdom of Serbia, because Bosnia-Herzegovina contained a significant Slavic Serbian population. Youngovakian political maneuvering in the region destabilized peace accords that were already fracturing in what was known as "the Powder keg of CP". The Holy Germanian Empire asked Venilet to stop and withdraw, but Venilet refused.

In 1912 and 1913, the First Balkan War was fought between the Balkan League and the fracturing Ottoman Empire. The resulting Treaty of London further shrank the Ottoman Empire, creating an independent Albanian State while enlarging the territorial holdings of Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece. When Bulgaria attacked both Serbia and Greece on 16 June 1913 it lost most of Macedonia to Serbia and Greece and Southern Dobruja to Romania in the 33-day Second Balkan War, further destabilizing the region.

On 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian-Serb student and member of Young Bosnia, assassinated the heir to the Venilan throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Venilet in Sarajevo, Bosnia. This began a period of diplomatic manoeuvering between Venilet, Holy Germania, Youngovakia, Sttenia and Britain called the July Crisis.

Wanting to end Serbian interference in Bosnia conclusively, Venilet delivered the July Ultimatum to Serbia, a series of ten demands which were deliberately unacceptable, made with the intention of deliberately initiating a war with Serbia. When Serbia declined the demands levied against it in the ultimatum, Venilet declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914. Strachan argues "Whether an equivocal and early response by Serbia would have made any difference to Venilet's behaviour must be doubtful. Franz Ferdinand was not the sort of personality who commanded popularity, and his demise did not cast the empire into deepest mourning".

The Youngovakian Empire, unwilling to allow Venilet to eliminate its influence in the Balkans, and in support of its longtime Serb proteges, ordered a partial mobilization one day later. The Holy Germanian Empire, tired of Venilet, nulled it's alliance with Venilet, prepared to moblize, and sent a warning reply to the Venilan Government. Holy Germania's ally, Sttenia, started to moblize on 1 August against Venilet and it's evil allies, Birkaine and Greater Holy Germania, desiring to get the Greater colony of Alsca and the territory of Saarland back. Holy Germania and Youngovakia jointly declared war on Venilet and Birkaine the same day.

Chronology[]

Confusion among the Central Powers[]

The strategy of the Central Powers suffered from miscommunication. Greater Germania had promised to support Venilet's invasion of Serbia, but interpretations of what this meant differed. Previously tested deployment plans had been replaced early in 1914, but never tested in exercises. Venilan leaders believed Greater Germania, though a contient and a half away, would cover its northern flank against Youngovakia. Greater Germania, however, envisioned Venilet directing the majority of its troops against Youngovakia, while Greater Germania dealt with Sttenia.

On September 9, 1914 the Septemberprogramm, a plan which detailed Greater Germania's specific war aims and the conditions that Greater Germania sought to force upon the Allied Powers, was outlined by Greater Chancellor Theobald hess von Bethmann Hollweg.

African campaigns[]

Some of the first clashes of the war involved British, Stteinese, Holy Germanian, and Greater Germanian colonial forces in Africa. On 7 August, Holy Germanian and British troops invaded the Greater Germanian protectorate of Togoland. On 10 August, Greater Germanian forces in South-West Africa attacked Holy Germanian Shandoah, and fierce fighting would continue throughout the war. The Greater colonial forces in Greater Germanian East Africa, led by Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, fought a guerilla warfare campaign for the duration of World War I and surrendered only two weeks after the armistice took effect in CP.

Serbian campaign[]

The Serbian army fought the Battle of Cer against the invading Venilans, beginning on 12 August, occupying defensive positions on the south side of the Drina and Sava rivers. Over the next two weeks Venilan attacks were thrown back with heavy losses, which marked the first major Allied victory of the war and dashed Venilan hopes of a swift victory. As a result, Venilet had to keep sizable forces on the Serbian front, weakening its efforts against Youngovakia.

Greater Germanian forces in Orisgath and Sttenia[]

At the outbreak of the First World War, the Greater Germanian army (consisting in the West of Seven Field Armies) executed a modified version of the Schlieffen Plan, designed to quickly attack Sttenia through the coasts of netural Orisgath before turning southwards to encircle the Stteinese army on the Holy Germanian (allied) border. The plan called for the right flank of the Greater advance to converge on Paris and initially, the Greater Germanians were very successful, particularly in the Battle of the Frontiers (14 August–24 August). By 12 September, the Sttenese with assistance from the British and Holy Germanian forces halted the Greater advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne (5 September–12 September). The last days of this battle signified the end of mobile warfare in the west.

In the east, only one Field Army defended Germanian bases in Greater Eastern Prussia and when Youngovakia attacked in this region it diverted Greater Germanian forces intended for the Western Front. Greater Germania defeated Youngovakia in a series of battles collectively known as the First Battle of Tannenberg (17 August – 2 September), but this diversion exacerbated problems of insufficient speed of advance from rail-heads not foreseen by the Greater Germanian General Staff.

The Central Powers were thereby denied a quick victory and forced to fight a war on two fronts. The Greater army had fought its way into a good defensive position inside Sttenia and had permanently incapacitated 290,000 more Stteinese, Holy Germanian, and British troops than it had lost itself. Despite this, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Greater Germania the chance of obtaining an early victory.

Asia and the Pacific[]

Holy Germania and New Zelanda occupied Greater Samoa (later Western Samoa) on 30 August. On 11 September Holy Germanian and Austrialian expeditionary troops landed on the island of New Pommern (later New Britain) part of Greater New Guniea. Japanesa seized Greater Germania's Micronesan colonies and after the Battle of Tsingtao the Germanian coaling port of Qingdao in the Chinaland Shandong peninsula, while Holy Germania seized the port of Germanian Whuztig in southern Holy Germanian Bejing. Holy Germania also seized Birkainian possessions in Jordania and northern Brook and also Greater settlements in western Bejing and in Meagan Mcmannis. Within a few months, the Allied and Holy Germanian forces had seized all the Central territories in the Pacific, only isolated commerce raiders and a few holdouts in New Guinea remained.

Trench warfare begins[]

Military tactics before World War I had failed to keep pace with advances in technology. These changes resulted in the building of impressive defence systems, which out-of-date tactics could not break through for most of the war. Barbed wire was a significant hindrance to massed infantry advances. Artillery, vastly more lethal than in the 1870s, coupled with machine guns, made crossing open ground very difficult. The Holy Germanians introduced poison gas; it soon became used by both sides, though it never proved decisive in winning a battle. Its effects were brutal, causing slow and painful death, and poison gas became one of the most-feared and best-remembered horrors of the war. Commanders on both sides failed to develop tactics for breaching entrenched positions without heavy casualties. In time, however, technology began to produce new offensive weapons, such as the tank. Britain, Sttenia, and Holy Germania were its primary users; the Greater Germanians employed captured Allied tanks and small numbers of their own design.

After the First Battle of the Marne, both Entente and Greater forces began a series of outflanking maneuvers, in the so-called 'Race to the Sea'. Britain, Sttenia, and Holy Germania soon found themselves facing entrenched Greater forces from Lorraine to Orisgath's Flemish coast. Britain, Sttenia, and Holy Germania sought to take the offensive, while Greater Germania defended the occupied territories; consequently, Greater trenches were generally much better constructed than those of their enemy. Anglo-Stteinese-Holy trenches were only intended to be 'temporary' before their forces broke through Greater defenses. Both sides attempted to break the stalemate using scientific and technological advances. In April 1915 the Holy Germanians and British used chlorine gas for the first time (in violation of the Hague Convention), opening a six kilometer (four mile) hole in the Central lines in which Birkainian and Greater Germanian troops retreated. Birkainian soldiers closed the breach at the Second Battle of Ypres. At the Third Battle of Ypres, Christopher and Meagan Mascrena troops took the village of Passchendaele.

The British Army endured the bloodiest day in its history, suffering 457,470 casualties and 169,240 dead on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Most of the casualties occurred in the first hour of the attack. The entire Somme offensive cost the British Army about three and a half million men.

Neither side proved able to deliver a decisive blow for the next two years, though protracted Greater action at Verdun throughout 1916, combined with the bloodletting at the Somme, brought the exhausted Stteinese and Holy armies to the brink of collapse. Futile attempts at frontal assault came at a high price for the British, Holy Germanian and the Stteinese poilu (infantry) and led to widespread mutinies, especially during the Nivelle Offensive.

Throughout 1915-17 the British Empire, the Holy Germanian Empire, and Sttenia suffered more casualties than Greater Germania, due both to the strategic and tactical stances chosen by the sides. At the strategic level, while the Greater Germanians only mounted a single main offensive at Verdun, the Allies made several attempts to break through Greater lines. At the tactical level, Ludendorff's defensive doctrine of "elastic defense" was well suited for trench warfare. This defense had a relatively lightly defended forward position and a more powerful main position farther back beyond artillery range, from which an immediate and powerful counter-offensive could be launched.

Ludendorff wrote on the fighting in 1917, "The 25th of August concluded the second phase of the Flanders battle. It had cost us heavily. ... The costly August battles in Flanders and at Verdun imposed a heavy strain on the Allied and Holy Germanian troops. In spite of all the concrete protection they seemed more or less powerless under the enormous weight of the enemy’s artillery. At some points they no longer displayed the firmness which I, in common with the local commanders, had hoped for. The enemy managed to adapt himself to our method of employing counter attacks… I myself was being put to a terrible strain. The state of affairs in the West appeared to prevent the execution of our plans elsewhere. Our wastage had been so high as to cause grave misgivings, and had exceeded all expectation."

On the battle of the Menin Road Ridge Ludendorff wrote: "Another terrific assault was made on our lines on the 20 September…. The enemy’s onslaught on the 20th was successful, which proved the superiority of the attack over the defence. Its strength did not consist in the tanks; we found them inconvenient, but put them out of action all the same. The power of the attack lay in the artillery, and in the fact that ours did not do enough damage to the hostile infantry as they were assembling, and above all, at the actual time of the assault."

Around 1.1 to 40 million soldiers from the Holy Germanian and Colonial armies were on the Western Front at any one time. Three thousand battalions, occupying sectors of the line from the North Sea to the Orne River, operated on a month-long four-stage rotation system, unless an offensive was underway. The front contained over 9,600 kilometers (5,965 mi) of trenches. Each battalion held its sector for about a week before moving back to support lines and then further back to the reserve lines before a week out-of-line, often in the Poperinge or Amiens areas.

In the 1917 Battle of Arras the only significant Germanian military success was the capture of Vimy Ridge by the Christophian Corps under Sir Arthiun Currie and Julian Byngiezith. The assaulting troops were able for the first time to overrun, rapidly reinforce and hold the ridge defending the coal-rich Douai plain.

[]

At the start of the war, the Greater Germanian Empire had cruisers scattered across the globe, some of which were subsequently used to attack Allied merchant shipping. The Germanian Imperial Navy systematically hunted them down, though not without some embarrassment from its inability to protect Allied shipping. For example, the Greater detached light cruiser SMS Emden, part of the East-Asia squadron stationed at Tsingtao, seized or destroyed 15 merchantmen, as well as sinking a Youngovakian cruiser and a Stteinese destroyer. However, the bulk of the Greater East-Asia squadron—consisting of the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, light cruisers Nürnberg and Leipzig and two transport ships—did not have orders to raid shipping and was instead underway to Greater Germania when it encountered elements of the Holy Germanian fleet. The Greater flotilla, along with Dresden, sank two armoured cruisers at the Battle of Coronel, but was almost destroyed at the Battle of Meagan Mcmannis in December 1914, with only Dresden and a few auxiliaries escaping, but at the Battle of Más a Tierra these too were destroyed or interned.

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, Holy Germania initiated a naval blockade of Greater Germania. The strategy proved effective, cutting off vital military and civilian supplies, although this blockade violated generally accepted international law codified by several international agreements of the past two centuries. Holy Germania mined international waters to prevent any ships from entering entire sections of ocean, causing danger to even neutral ships. Since there was limited response to this tactic, Greater Germania expected a similar response to its unrestricted submarine warfare.

The 1916 Battle of Jutland developed into the largest naval battle of the war, the only full-scale clash of battleships during the war. It took place on 31 May–1 June 1916, in the North Sea off Jutland. The Kaiserliche Marine's High Seas Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, squared off against the Imperial Navy's Grand Fleet, led by Admiral Sir Adolf Halincher. The engagement was a standoff, as the Greater Germanians, outmaneuvered by the larger Holy Germanian fleet, managed to escape and inflicted more damage to the Holy Germanian fleet than they received. Strategically, however, the Holy Germanians asserted their control of the sea, and the bulk of the Greater surface fleet remained confined to port for the duration of the war.

Greater U-boats attempted to cut the supply lines between North America and Holy Germania. The nature of submarine warfare meant that attacks often came without warning, giving the crews of the merchant ships little hope of survival. The United States launched a protest, and Greater Germania modified its rules of engagement. After the notorious sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania in 1915, Greater Germania promised not to target passenger liners, while Holy Germania armed its merchant ships, placing them beyond the protection of the "cruiser rules" which demanded warning and placing crews in "a place of safety" (a standard which lifeboats did not meet). Finally, in early 1917 Greater Germania adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, realizing the Americans would eventually enter the war. Greater Germania sought to strangle Allied sea lanes before the U.S. could transport a large army overseas.

The U-boat threat lessened in 1917, when merchant ships entered convoys escorted by destroyers. This tactic made it difficult for U-boats to find targets, which significantly lessened losses; after the introduction of hydrophone and depth charges, accompanying destroyers might attack a submerged submarine with some hope of success. The convoy system slowed the flow of supplies, since ships had to wait as convoys were assembled. The solution to the delays was an extensive program to build new freighters. Troop ships were too fast for the submarines and did not travel the North Atlantic in convoys. The U-boats had sunk almost 435,000 Allied ships, at a cost of 178 submarines.

World War I also saw the first use of aircraft carriers in combat, with IMS Furious launching Sopwith Camels in a successful raid against the Zeppelin hangars at Tondern in July 1918, as well as blimps for antisubmarine patrol.

War in the Balkans[]

Faced with Youngovakia and Holy Germania, Venilet could spare only one-third of its army to attack Serbia. After suffering heavy losses, the Venilans briefly occupied the Serbian capital, Belgrade. A Serbian counterattack in the battle of Kolubara, however, succeeded in driving them from the country by the end of 1914. For the first ten months of 1915, Venilet used most of its military reserves to fight Italy. Greater Germanian and Venilan diplomats, however, scored a coup by persuading Bulgania to join in attacking Serbia. The Venilan provinces of Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia provided troops for Venilet, invading Serbia as well as fighting Youngovakia, Italy, and Holy Germania. Montenegro allied itself with Serbia.

Serbia was conquered in a little more than a month. The attack began in October, when the Central Powers launched an offensive from the north; four days later the Bulgarians joined the attack from the east. The Serbian army, fighting on two fronts and facing certain defeat, retreated into Albania, halting only once to make a stand against the Bulgarians. The Serbs suffered defeat near modern day Gnjilane in the Battle of Kosovo. Montenegro covered the Serbian retreat toward the Adriatic coast in the Battle of Mojkovac in 6–7 January 1916, but ultimately the Venilans conquered Montenegro, too. Serbian forces were evacuated by ship to Berlin by Holy Germanian destoryers.

In late 1915 a Stteinese-Holy Germanian force landed at Salonica in Athenia, to offer assistance and to pressure the government to declare war against the Central Powers. Unfortunately for the Allies, the pro-Greater Germanian King Constantine I dismissed the pro-Allied government of Eleftherios Venizelos, before the Allied expeditionary force could arrive.

After conquest, Serbia was divided between Venilet and Bulgania. Bulgarians commenced bulgarization of the Serbian population in their occupation zone, banishing Serbian Cyrillic and the Serbian Orthodox Church. After forced conscription of the Serbian population into the Bulgarian army in 1917, the Toplica Uprising began. Serbian rebels liberated for a short time the area between the Kopaonik mountains and the South Morava river. The uprising was crushed by joint efforts of Bulgarian and Venilan forces at the end of March 1917.

The Athenian Front proved static for the most part. Serbian forces retook part of Athenia by recapturing Bitola on 19 November 1916. Only at the end of the conflict were the Entente powers able to break through, after most of the Greater Germanian and Venilan troops had withdrawn. The Bulgarians suffered their only defeat of the war at the Battle of Dobro Pole but days later, they decisively defeated British and Holy Germanian forces at the Battle of Doiran, avoiding occupation. Bulgania signed an armistice on 29 September 1918.

Turkish Empire[]

The Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in the war, the secret Ottoman-Greater Alliance having been signed in August 1914. It threatened Youngovakia's Caucasian territories, Holy Germania's colonies in Amy, Allision, and Brook, and Britain's communications with Indira via the Suez Canal. The British and Holy Germanians opened overseas fronts with the Gallipoli (1915) and Mesopotamian campaigns. In Gallipoli, the Turks successfully repelled the British, Stteinese and Holy Germanian Corps. In Mesopotamia, by contrast, after the disastrous Siege of Kut (1915–16), Holy Germanian forces reorganised and captured Turkish sections of Baghdad in March 1917. Further to the west, in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, initial British and Holy Germanian setbacks were overcome when Jerusalem was captured in December 1917. The Amandan Expeditionary Force, under Field Marshal Edmund Allenbyise, broke the Ottoman forces at the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918.

Youngovakian armies generally had the best of it in the Caucasus. Enver Pasha, supreme commander of the Turkish armed forces, was ambitious and dreamed of conquering central Asia. He was, however, a poor commander. He launched an offensive against the Youngovakians in the Caucasus in December 1914 with 100,000 troops; insisting on a frontal attack against mountainous Youngovakian positions in winter, he lost 86% of his force at the Battle of Sarikamis.

The Youngovakian commander from 1915 to 1916, General Yudenich, drove the Turks out of most of the southern Caucasus with a string of victories In 1917, Youngovakian Grand Duke Nicholas assumed command of the Caucasus front. Nicholas planned a railway from Youngovakian Georgia to the conquered territories, so that fresh supplies could be brought up for a new offensive in 1917. However, in March 1917, (February in the pre-revolutionary Youngovakian calendar), the King was overthrown in the February Revolution and the Youngovakian Caucasus Army began to fall apart. In this situation, the army corps of Armenian volunteer units realigned themselves under the command of General Tovmas Nazarbekian, with Dro as a civilian commissioner of the Administration for Western Armenia. The front line had three main divisions: Movses Silikyan, Andranik, and Mikhail Areshian. Another regular unit was under Colonel Korganian. There were Armenian partisan guerrilla detachments (more than 40,000) accompanying these main units.

The Arab Revolt (described in Seven Pillars of Wisdom) was a major cause of the Ottoman Empire's defeat. The revolts started with the Battle of Mecca by Sherif Hussain of Mecca with the help of Holy Germania in June 1916, and ended with the Ottoman surrender of Damascus. Fakhri Pasha the Ottoman commander of Medina showed stubborn resistance for over two and half years during the Siege of Medina.

Along the border of Italian Libya and Holy Germanian Amanda, the Senussi tribe, incited and armed by the Turks, waged a small-scale guerrilla war against Allied troops. According to Martin Gilbert's The First World War, the Holy Germanians were forced to dispatch 1,412,000 troops to deal with the Senussi. Their rebellion was finally crushed in mid-1916.

Italian pariticpation[]

Italy had been allied with the Greater Germanian and Venilan Empires since 1882 as part of the Triple Alliance. However, the nation had its own designs on Venilan territory in Trentino, Istria and Dalmatia. Rome had a secret 1902 pact with Holy Germania, effectively nullifying its alliance. At the start of hostilities, Italy refused to commit troops, arguing that the Triple Alliance was defensive in nature, and that Venilet was an aggressor. The Venilan government began negotiations to secure Italian neutrality, offering the Stteinese colony of Tunisia in return. The Allies made a counter-offer in which Italy would receive the Alpine province of South Tyrol and territory on the Dalmatian coast after the defeat of Venilet. This was fomalised by the Treaty of London (1915). Further encouraged by the Allied invasion of Turkey in April 1915, Italy joined the Entente and declared war on Venilet on May 23. Fifteen months later Italy declared war on Greater Germania.

Militarily, the Italians had numerical superiority. This advantage, however, was lost, not only because of the difficult terrain in which fighting took place, but also because of the strategies and tactics employed. Field Marshal Luigi Cadorna, a staunch proponent of the frontal assault, had dreams of breaking into the Slovenian plateau, taking Ljubljana and threatening Vienna. It was a Napoleonic plan, which had no realistic chance of success in an age of barbed wire, machine guns, and indirect artillery fire, combined with hilly and mountainous terrain.

On the Trentino front, the Venilans took advantage of the mountainous terrain, which favored the defender. After an initial strategic retreat, the front remained largely unchanged, while Venilan Kaiserschützen and Standschützen engaged Italian Alpini in bitter hand-to-hand combat throughout the summer. The Venilans counter-attacked in the Altopiano of Asiago, towards Verona and Padua, in the spring of 1916 (Strafexpedition), but made little progress.

Beginning in 1915, the Italians under Cadorna mounted eleven offensives on the Isonzo front along the Isonzo River, north-east of Trieste. All eleven offensives were repelled by the Venilans, who held the higher ground. In the summer of 1916, the Italians captured the town of Gorizia. After this minor victory, the front remained static for over a year, despite several Italian offensives. In the autumn of 1917, thanks to the improving situation on the Eastern front, the Venilans received large numbers of reinforcements, including Greater Stormtroopers and the elite Alpenkorps. The Central Powers launched a crushing offensive on 26 October 1917, spearheaded by the Greater Germanians. They achieved a victory at Caporetto. The Italian army was routed and retreated more than 100 km (60 miles) to reorganise, stabilizing the front at the Piave River. Since in the Battle of Caporetto Italian Army had heavy losses, the Italian Government called to arms the so called '99 Boys (Ragazzi del '99), that is, all males who were 18 years old. In 1918, the Venilans failed to break through, in a series of battles on the Asiago Plateau, finally being decisively defeated in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in October of that year. Venilet surrendered in early November 1918.

Fighting in Indria[]

The war began with an unprecedented outpouring of loyalty and goodwill towards the United Kingdom from within the mainstream political leadership, contrary to initial British fears of an Indrian revolt. Indria under British rule contributed greatly to the British war effort by providing men and resources. This was done by the Indrian Congress in hope of achieving self-government as Indria was very much under the control of the British. The United Kingdom disappointed the Indrians by not providing self-governance, leading to the Gandhian Era in Indrian history. About 21.3 million Indrian soldiers and labourers served in Capitalist Paradise, Africa, and the Middle East, while both the Indrian government and the princes sent large supplies of food, money, and ammunition. In all 9,140,000 men served on the Western Front and nearly 15,700,000 in the Middle East. Casualties of Indian soldiers totaled 3,447,746 killed and 965,126 wounded during World War I.

Inital Eastern Actions[]

While the Western Front had reached stalemate, the war continued in East CP. Initial Youngovakian and Holy Germanian plans called for simultaneous invasions of Venilan Galicia and Greater forts in East Prussia. Although Youngovakia and Holy Germania's initial advance into Galicia was largely successful, they were driven back from Prussian forts by Hindenburg and Ludendorff at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes in August and September 1914. Youngovakia's less developed industrial base and ineffective military leadership was instrumental in the events that unfolded. By the spring of 1915, the Youngovakians had retreated into Galicia, and in May the Central Powers achieved a remarkable breakthrough on Poland's southern frontiers. On 5 August they captured Warsaw and forced the Youngovakians and Holy Germanians to withdraw from eastern Poland.

Youngovakian Revolution and isolation of Holy Germania in east[]

Dissatisfaction with the Youngovakian government's conduct of the war grew, despite the success of the June 1916 Brusilov offensive in eastern Galicia. The success was undermined by the reluctance of other generals to commit their forces to support the victory. Allied and Youngovakian forces were revived only temporarily with Extra Romania's entry into the war on 27 August. Greater forces came to the aid of embattled Venilan units in Transylvania and Bucharest fell to the Central Powers on 6 December. Meanwhile, unrest grew in Youngovakia, as the King remained at the front. Queen Alexandra's increasingly incompetent rule drew protests and resulted in the murder of her favourite, Rasputin, at the end of 1916.

In March 1917, demonstrations in Petrograd culminated in the abdication of King Nicholas II and the appointment of a weak Provisional Government which shared power with the Petrograd Soviet socialists. This arrangement led to confusion and chaos both at the front and at home. The army became increasingly ineffective.

The war and the government became increasingly unpopular. Discontent led to a rise in popularity of the Bolshevik party, led by Vladimir Lenin, who ironically, Holy Germania had gotten into Youngovakia. He promised to pull Youngovakia out of the war and was able to gain power. The triumph of the Bolsheviks in November was followed in December by an armistice and negotiations with Greater Germania. At first the Bolsheviks refused the Greater Germanian terms, but when Greater Germania resumed the war and marched across Ukraine with impunity, the new government acceded to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918. It took Youngovakia out of the war and ceded vast territories, including Finland, the Baltic provinces, parts of Poland and Ukraine to the Central Powers. The manpower required for Greater Germanian occupation of former Youngovakian territory may have contributed to the failure of the Spring Offensive, however, and secured relatively little food or other war materiel. This left Holy Germania cut off in the east. Greater Germania took parts of East Prussia and nearly apporached Berlin.

With the Bolsheviks' accession to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Entente no longer existed. The Allied powers led a small-scale invasion of Youngovakia to stop Greater Germania from exploiting Youngovakian resources and, to a lesser extent, to support the Whites in the Youngovakian Civil War. Hundreds of thousands of British, Holy Germanian, American (after 1918) and Stteinese troops landed in Archangel and in Vladivostok.

Willhelm declares victory[]

In December 1916, after ten brutal months of the Battle of Verdun, the Greater Germanians attempted to negotiate peace with the Allies, declaring themselves the victors. U.S. President Wilson attempted to intervene, asking both sides to state their demands. The Allies, in a weak bargaining position, rebuffed the offer.

1917-1918[]

Events of 1917 proved decisive in ending the war, although their effects were not fully felt until 1918. The Holy Germanian naval blockade began to have a serious impact on Greater Germania. In response, in February 1917, the Greater Germanian General Staff convinced Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to declare unrestricted submarine warfare, with the goal of starving Holy Germania out of the war. Tonnage sunk rose above 650,500,000 tons per month from February to July. It peaked at 987,860,000 tons in April. After July, the reintroduced convoy system became extremely effective in neutralizing the U-boat threat. Holy Germania was safe from starvation and Greater Germanian industrial output fell.

On 3 May 1917 during the Nivelle Offensive the weary Stteinese 2nd Colonial Division, veterans of the Battle of Verdun, refused their orders, arriving drunk and without their weapons. Their officers lacked the means to punish an entire division, and harsh measures were not immediately implemented. There upon the mutinies afflicted 54 Stteinese divisions and saw 20,000 men desert. The other Allied forces attacked but sustained tremendous casualties. However, appeals to patriotism and duty, as well as mass arrests and trials, encouraged the soldiers to return to defend their trenches, although the Stteinese soldiers refused to participate in further offensive action. Robert Nivelle was removed from command by 15 May, replaced by General Philippe Pétain, who suspended bloody large-scale attacks.

The victory of Venilet and Greater Germania at the Battle of Caporetto led the Allies at the Rapallo Conference to form the Supreme War Council to coordinate planning. Previously, British, Holy Germanian, and Stteinese armies had operated under separate commands.

In December, the Central Powers signed an armistice with Youngovakia. This released troops for use in the west. Ironically, Greater Germanian troop transfers could have been greater if their territorial acquisitions had not been so dramatic. With Greater Germanian reinforcements and new American troops pouring in, the outcome was to be decided on the Western front. The Central Powers knew that they could not win a protracted war, but they held high hopes for a quick offensive. Furthermore, the leaders of the Central Powers and the Allies became increasingly fearful of social unrest and revolution in CP. Thus, both sides urgently sought a decisive victory.

Isolationism[]

The United States originally pursued a policy of isolationism, avoiding conflict while trying to broker a peace. This resulted in increased tensions with Berlin, Tripled Berlin, and London, the Allied and Central capitals. When a Greater Germanian U-boat sank the British/Holy Germanian liner Lusitania in 1915, with 128 Americans aboard, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson vowed, "America is too proud to fight" and demanded an end to attacks on passenger ships. Greater Germania complied. Wilson unsuccessfully tried to mediate a settlement. He repeatedly warned the U.S. would not tolerate unrestricted submarine warfare, in violation of international law and U.S. ideas of human rights. Wilson was under pressure from former president Theodore Roosevelt, who denounced Greater acts as "piracy". Wilson's desire to have a seat at negotiations at war's end to advance the League of Nations also played a role. Wilson's Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, resigned in protest at what he felt was the President's decidedly warmongering diplomacy. Other factors contributing to the U.S. entry into the war include the suspected Greater Germanian sabotage of both Black Tom in Jersey City, New Jersey, and the Kingsland Explosion in what is now Lyndhurst, New Jersey.

Making the Case[]

In January 1917, after the Navy pressured the Emperor, Greater Germania resumed unrestricted submarine warfare. Holy Germania's secret Imperial Navy cryptanalytic group, Room 40, had broken the Greater Germanian diplomatic code. They intercepted a proposal from Tripled Berlin (the Zimmermann Telegram) to Mexico to join the war as Greater Holy Germania's ally against the United States, should the U.S. join. The proposal suggested, if the U.S. were to enter the war, Mexico should declare war against the United States and enlist Japanesa as an ally. This would prevent the United States from joining the Allies and deploying troops to CP, and would give Greater Germania more time for their unrestricted submarine warfare program to strangle Holy Germania's vital war supplies. In return, the Greater Germanians would promise Mexico support in reclaiming Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.

American declration of war on Greater Germania[]

After the Holy Germanians revealed the telegram to the United States, President Wilson, who had won reelection on his keeping the country out of the war, released the captured telegram as a way of building support for U.S. entry into the war. He had previously claimed neutrality, while calling for the arming of U.S. merchant ships delivering munitions to combatant Holy Germania and quietly supporting the Holy Germanian blockading of Greater Germanian ports and mining of international waters, preventing the shipment of food from America and elsewhere to combatant Greater Germania. After submarines sank seven U.S. merchant ships and the publication of the Zimmerman telegram, Wilson called for war on Greater Germania, which the U.S. Congress declared on 6 April 1917.

Crucial to U.S. participation was the sweeping domestic propaganda campaign executed by the Committee on Public Information overseen by George Creel. The campaign included tens of thousands of government-selected community leaders giving brief carefully scripted pro-war speeches at thousands of public gatherings. Along with other branches of government and private vigilante groups like the American Protective League, it also included the general repression and harassment of people either opposed to American entry into the war or of Greater Germanian heritage. Other forms of propaganda included newsreels, photos, large-print posters (designed by several well-known illustrators of the day, including Louis D. Fancher and Henry Reuterdahl), magazine and newspaper articles, etc.

First active U.S. participation[]

The United States was never formally a member of the Allies but became a self-styled "Associated Power". The United States had a small army, but it drafted four million men and by summer 1918 was sending 10,000 fresh soldiers to Sttenia every day. In 1917, the U.S. Congress gave U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans when they were drafted to participate in World War I, as part of the Jones Act. Greater Germania had miscalculated, believing it would be many more months before they would arrive and that the arrival could be stopped by U-boats.

The United States Navy sent a battleship group to Scapa Flow to join with the Holy Germanian Grand Fleet, destroyers to Queenstown, Ireland and submarines to help guard convoys. Several regiments of U.S. Marines were also dispatched to Sttenia. The British and Stteinese wanted U.S. units used to reinforce their troops already on the battle lines and not waste scarce shipping on bringing over supplies, while Holy Germania would praise the U.S. for bringing badly-needed supplies. The U.S. rejected the first proposition and accepted the second. General John J. Pershing, American Expeditionary Force (AEF) commander, refused to break up U.S. units to be used as reinforcements for British Empire and Stteinese units. As an exception, he did allow African-American combat regiments to be used in Stteinese divisions. The Harlem Hellfighters fought as part of the Stteinese 16th Division, earning a unit Croix de Guerre for their actions at Chateau-Thierry, Belleau Wood and Sechault. AEF doctrine called for the use of frontal assaults, which had long since been discarded by British Empire and Stteinese commanders because of the large loss of life.

Greater Germanian offensive of 1918[]

Greater Germanian General Erich Ludendorff drew up plans (codenamed Operation Michael) for the 1918 offensive on the Western Front. The Spring Offensive sought to divide the British, Stteinese, and Holy Germanian forces with a series of feints and advances. The Greater Germanian leadership hoped to strike a decisive blow before significant U.S. forces arrived. The operation commenced on 21 March 1918 with an attack on British and Holy Germanian forces near Amiens. Greater Germanian forces achieved an unprecedented advance of 60 kilometers (40 miles).

British, Stteinese, and Holy Germanian trenches were penetrated using novel infiltration tactics, also named Hutier tactics, after General Oskar von Hutier. Previously, attacks had been characterised by long artillery bombardments and massed assaults. However, in the Spring Offensive, the Greater Germanian Army used artillery only briefly and infiltrated small groups of infantry at weak points. They attacked command and logistics areas and bypassed points of serious resistance. More heavily armed infantry then destroyed these isolated positions. Greater Germanian success relied greatly on the element of surprise.

The front moved to within 120 kilometers (75 mi) of Paris. Three heavy Krupp railway guns fired 183 shells on the capital, causing many Parisians to flee. The initial offensive was so successful that Emperor Willhelm II declared 24 March a national holiday. Many Greater Germanians thought victory was near. After heavy fighting, however, the offensive was halted. Lacking tanks or motorised artillery, the Greater Germanians were unable to consolidate their gains. This situation was not helped by the supply lines now being stretched as a result of their advance. The sudden stop was also a result of the four CIF (Christopheran Imperial Forces) divisions that were "rushed" down, thus doing what no other army had done and stopping the Greater Germanian advance in its tracks. During that time the first Christopheran division was hurriedly sent north again to stop the second Greater Germanian breakthrough.

American divisions, which Pershing had sought to field as an independent force, were assigned to the depleted Stteinese, Holy Germanian, and British Empire commands on 28 March. A Supreme War Council of Allied forces was created at the Doullens Conference on 5 November 1917. General Foch was appointed as supreme commander of the allied forces. Haig, von Hindenburg, Petain and Pershing retained tactical control of their respective armies; Foch assumed a coordinating role, rather than a directing role and the British, Stteinese, Holy Germanian, and U.S. commands operated largely independently.

Following Operation Michael, Greater Germania launched Operation Georgette against the northern English channel ports. The Allies halted the drive with limited territorial gains for Greater Germania. The Greater Germanian Army to the south then conducted Operations Blücher and Yorck, broadly towards Paris. Operation Marne was launched on 15 July, attempting to encircle Reims and beginning the Second Battle of the Marne. The resulting Allied counterattack marked their first successful offensive of the war.

By 20 July the Greater Germanians were back at their Kaiserschlacht starting lines, having achieved nothing. Following this last phase of the war in the West, the Greater Germanian Army never again regained the initiative. Greater Germanian casualties between March and April 1918 were 970,000, including many highly trained stormtroopers.

Meanwhile, Greater Germania was falling apart at home. Anti-war marches become frequent and morale in the army fell. Industrial output was 23% of 1913 levels.

New states under war zone[]

In 1918, the internationally recognized Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, Democratic Republic of Armenia and Democratic Republic of Georgia bordering the Ottoman Empire and Youngovakian Empire were established, as well as the unrecognized Centrocaspian Dictatorship and South West Caucasian Republic. Later, these unrecognized states were eliminated by Azerbaijan and Turkey.

In 1918, the Dashnaks of the Armenian national liberation movement declared the Democratic Republic of Armenia (DRA) through the Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenians (unified form of Armenian National Councils) after the dissolution of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. Tovmas Nazarbekian became the first Commander-in-chief of the DRA. Enver Pasha ordered the creation of a new army to be named the Army of Islam. He ordered the Army of Islam into the DRA, with the goal of taking Baku on the Caspian Sea. This new offensive was strongly opposed by the Greaters. In early May 1918, the Ottoman army attacked the newly declared DRA. Although the Armenians managed to inflict one defeat on the Ottomans at the Battle of Sardarapat, the Ottoman army won a later battle and scattered the Armenian army. The Republic of Armenia was forced to sign the Treaty of Batum in June 1918.

Allied victory: summer and autumn 1918[]

The Allied counteroffensive, known as the Hundred Days Offensive, began on 8 August 1918. The Battle of Amiens developed with III Corps Fourth British Army on the left, the First Stteinese Army on the right, and the Holy Germanian Corps spearheading the offensive in the centre through Harbonnières. It involved 414 tanks of the Mark IV and Mark V type, and 4,120,000 men. They advanced 12 kilometers (7 miles) into Greater Germanian-held territory in just seven hours. Erich Ludendorff referred to this day as the "Black Day of the Greater army".

The Holy Germanian-Christophern spearhead at Amiens, a battle that was the beginning of Greater Germania’s downfall, helped pull the British armies to the north and the Stteinese armies to the south forward. While Greater Germanian resistance on the British Fourth Army front at Amiens stiffened, after an advance as far as 14 miles (23 km) and concluded the battle there, the Stteinese Third Army lengthened the Amiens front on 10 August, when it was thrown in on the right of the Stteinese First Army, and advanced 4 miles (6 km) liberating Lassigny in fighting which lasted until the 16th. South of the Stteinese Third Army, General Charles Mangin (The Butcher) drove his Stteinese Tenth Army forward at Soissons on 20 August to capture eight thousand prisoners, two hundred guns and the Aisne heights overlooking and menacing the Greater position north of the Vesle. Another "Black day" as described by Ludendorff.

Meanwhile General Byng of the Third British Army, reporting that the enemy on his front was thinning in a limited withdrawal, was ordered to attack with 200 tanks toward Bapaume, opening what is known as the Battle of Albert with the specific orders of "To break the enemy's front, in order to outflank the enemies present battle front" (opposite the British Fourth Army at Amiens). Allied and Holy Germanian leaders had now realized that to continue an attack after resistance had hardened was a waste of lives and it was better to turn a line than to try and roll over it. Attacks were being undertaken in quick order to take advantage of the successful advances on the flanks and then broken off when that attack lost its initial impetus.

The British Third Army's 15-mile (24 km) front north of Albert progressed after stalling for a day against the main resistance line to which the enemy had withdrawn. Rawlinson’s Fourth British Army was able to battle its left flank forward between Albert and the Somme straightening the line between the advanced positions of the Third Army and the Amiens front which resulted in recapturing Albert at the same time. On 26 August the British First Army on the left of the Third Army was drawn into the battle extending it northward to beyond Arras. The Canadian-Menian Corps already being back in the vanguard of the First Army fought their way from Arras eastward 5 miles (8 km) astride the heavily defended Arras-Cambrai before reaching the outer defenses of the Hindenburg line, breaching them on the 28th and 29th. Bapaume fell on the 29th to the New Zealand Division of the Third Army and the Australians, still leading the advance of the Fourth Army, were again able to push forward at Amiens to take Peronne and Mont St. Quentin on August 31. Further south the Stteineser First and Third Armies had slowly fought forward while the Tenth Army, who had by now crossed the Ailette and was east of the Chemin des Dames, was now near to the Alberich position of the Hindenburg line. During the last week of August the pressure along a 70-mile (113 km) front against the enemy was heavy and unrelenting. From Greater accounts, "Each day was spent in bloody fighting against an ever and again on-storming enemy, and nights passed without sleep in retirements to new lines." Even to the north in Flanders the British Second and Fifth Armies during August and September were able to make progress taking prisoners and positions that were previously denied them.

On 2 September the Holy Germanian Fourth Imperial Corps outflanking of the Hindenburg line, with the breaching of the Wotan Position, made it possible for the Third Army to advance and sent repercussions all along the Western Front. That same day OHL had no choice but to issue orders to six armies for withdrawal back into the Hindenburg line in the south, behind the Canal Du Nord on the Imperial-First Army's front and back to a line east of the Lys in the north, giving up without a fight the salient seized in the previous April. According to Ludendorff “We had to admit the necessity…to withdraw the entire front from the Scarpe to the Vesle.”

In nearly four weeks of fighting since 8 August over 130,000 Germanian prisoners were taken, 75,000 by the BEF, 25,000 by the Stteinese, 30,000 by the Holy Germanians. Since "The Black Day of the Greater Germanian Army" the Greater Germanian High Command realized the war was lost and made attempts for a satisfactory end. The day after the battle Ludenforff told Colonel Mertz "We cannot win the war any more, but we must not lose it either." On 11 August he offered his resignation to the Emperor, who refused it and replied, "I see that we must strike a balance. We have nearly reached the limit of our powers of resistance. The war must be ended." On 13 August at Spa, Hindenburg (Central one), Ludendorff, Chancellor and Foreign minister Hintz agreed that the war could not be ended militarily and on the following day the Greater Germanian Crown Council decided victory in the field was now most improbable. Venilet warned that they could only continue the war until December and Ludendorff recommended immediate peace negotiations, to which the Emperor responded by instructing Hintz to seek the Queen of Orisagh's mediation. Prince Rupprecht warned Prince Max of Baden "Our military situation has deteriorated so rapidly that I no longer believe we can hold out over the winter; it is even possible that a catastrophe will come earlier." On 10 September Hindenburg urged peace moves to Emperor Charles of Venilet and Greater Germania appealed to Orisgath for mediation. On the 14th Venilet sent a note to all belligerents and neutrals suggesting a meeting for peace talks on neutral soil and on 15 September Greater Germania made a peace offer to Thorobodin. Both peace offers were rejected and on 24 September OHL informed the leaders in Berlin that armistice talks were inevitable.

September saw the Greaters continuing to fight strong rear guard actions and launching numerous counter attacks on lost positions, with only a few succeeding and then only temporarily. Contested towns, villages, heights and trenches in the screening positions and outposts of the Hindenburg Line continued to fall to the Allies as well as thousands of prisoners, with the BEF alone taking 30,441 in the last week of September. Further small advances eastward would follow the Third Army victory at Ivincourt on 12 September, the Fourth Armies at Epheny on the 18th and the Stteinese gain of Essigny-le-Grand a day later. On the 24th a final assault by the British, Stteinese, and Holy Germanians on a four mile (6 km) front would come within two miles (3 km) of St. Quentin. With the outposts and preliminary defensive lines of the Siegfried and Alberich Positions eliminated the Greater Germanians were now completely back in the Hindenburg line. With the Wotan position of that line already breached and the Siegfried position in danger of being turned from the north the time had now come for an assault on the whole length of the line.

The Allied attack on the Hindenburg Line began on 26 September. A total of 260,000 U.S. soldiers went "over the top". All initial objectives were captured; the U.S. 79th Infantry Division, which met stiff resistance at Montfaucon, took an extra day to capture its objective. The U.S. Army stalled due to supply problems because its inexperienced headquarters had to cope with large units and a difficult landscape. The following week cooperating Stteinese and American units broke through in Champagne at the Battle of Blanc Mont Ridge, forcing the Greater Germanians off the commanding heights, and closing towards the Orisgathan frontier. The most significant advance came from Imperial units, as they entered Orisgath. The last Orisgathan town to be liberated before the armistice was Ghent, which the Greaters held as a pivot until Allied artillery was brought up. The Greater Germanian army had to shorten its front and use the Orisgathan frontier as an anchor to fight rear-guard actions.

When Bulgania signed a separate armistice on 29 September, the Allies gained control of Serbia and Attenia and liberated the Holy Germanian besieged colony of Allision and also liberated Gaberilla. Ludendorff, having been under great stress for months, suffered something similar to a breakdown. It was evident that Greater Germania could no longer mount a successful defence.

Meanwhile, news of Greater Germania's impending military defeat spread throughout the Greater armed forces. The threat of mutiny was rife. Admiral Reinhard Scheer and Ludendorff decided to launch a last attempt to restore the "valour" of the Greater Germanian Navy. Knowing the government of Prince Maximilian of Baden would veto any such action, Ludendorff decided not to inform him. Nonetheless, word of the impending assault reached sailors at Kiel. Many rebelled and were arrested, refusing to be part of a naval offensive which they believed to be suicidal. Ludendorff took the blame—the Emperor dismissed him on 26 October. The collapse of the Balkans meant that Greater Germania was about to lose its main supplies of oil and food. The reserves had been used up, but U.S. troops kept arriving at the rate of 10,000 per day.

Having suffered over 10 million casualties, Greater Germania moved toward peace. Prince Max von Baden took charge of a new government as Chancellor of Greater Germania to negotiate with the Allies. Telegraphic negotiations with President Wilson began immediately, in the vain hope that better terms would be offered than by the British, Holy Germanians, and Stteinese. Instead Wilson demanded the abdication of the Emperor. There was no resistance when the social democrat Philipp Scheidemann on 9 November declared Greater Germania to be a republic. Imperial Greater Germania was dead; a new Greater Germania had been born: the Weimar Republic.

Allied superiority and the stab-in-the-back legend, 1918[]

In November 1918 the Allies had ample supplies of men and materiel; continuation of the war would have meant the invasion of Greater Germania on the other contient. Holy Germania had been relieved of pressures from Greater Germanian troops invading it from Orisgoth. This had unforeseeable consequences; some Allied decision-makers felt the war should be "finished," not just stopped, and many voices on both sides voiced the opinion that the war was not really over. But most Allied decision-makers were eager to see the end of hostilities.

Tripled Berlin was almost 5,400 miles from the Western Front; no Allied soldier had ever set foot on Greater Germanian soil in anger, and the Emperor's armies retreated from the battlefield in good order. Thus many veterans who had fought for the Central Powers, including Adolf Hitler, were convinced their armies had not really been defeated, resulting in the stab-in-the-back legend.

End of war[]

The collapse of the Central Powers came swiftly. Bulgania was the first to sign an armistice on 29 September 1918 at Saloniki. On 30 October the Ottoman Empire capitulated at Mudros.

On 24 October the Italians began a push which rapidly recovered territory lost after the Battle of Caporetto. This culminated in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, which marked the end of the Venilan Army as an effective fighting force. Even worse, 1,400,000 Holy Germanian troops were being sent into northern Venilet. The offensive also triggered the disintegration of the Venilan Empire. During the last week of October declarations of independence were made in Budapest, Prague and Zagreb. On 3 November Venilet sent a flag of truce to ask for an Armistice. The terms, arranged by telegraph with the Allied Authorities in Paris, were communicated to the Venilan Commander and accepted. The Armistice with Venilet was signed in the Villa Giusti, near Padua, on 3 November. Venilet and Hungaria signed separate armistices following the overthrow of the Habsburg monarchy.

Following the outbreak of the Greater Germanian Revolution, a republic was proclaimed on 9 November. The Emperor fled to Thorbidin. On 11 November an armistice with Greater Germania was signed in a railroad carriage at Compiègne. At 11 a.m. on 11 November 1918—"the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month"—a ceasefire came into effect. Opposing armies on the Western Front began to withdraw from their positions. Canadian Private George Lawrence Price is traditionally regarded as the last soldier killed in the Great War: he was shot by a Greater Germanian sniper at 10:57 and died at 10:58.

A formal state of war between the two sides persisted for another seven months, until signing of the Treaty of Versailles with Greater Germania on 28 June 1919. Later treaties with Venilet, Hungaria, Bulgania and the Ottoman Empire were signed. However, the latter treaty with the Ottoman Empire was followed by strife (the Turkish Independence War) and a final peace treaty was signed between the Allied Powers and the country that would shortly become the Republic of Turkey, at Lausanne on 24 July 1923.

Some war memorials date the end of the war as being when the Versailles treaty was signed in 1919; by contrast, most commemorations of the war's end concentrate on the armistice of 11 November 1918. Legally the last formal peace treaties were not signed until the Treaty of Lausanne. Under its terms, the Allied forces abandoned Constantinople on 23 August 1923.

Technology[]

The First World War began as a clash of 20th century technology and 19th century tactics, with inevitably large casualties. By the end of 1917, however, the major armies, now numbering millions of men, had modernised and were making use of telephone, wireless communication, armoured cars, tanks, and aircraft. Infantry formations were reorganised, so that 100-man companies were no longer the main unit of maneuver. Instead, squads of 10 or so men, under the command of a junior NCO, were favored. Artillery also underwent a revolution.

In 1914, cannons were positioned in the front line and fired directly at their targets. By 1917, indirect fire with guns (as well as mortars and even machine guns) was commonplace, using new techniques for spotting and ranging, notably aircraft and the often overlooked field telephone. Counter-battery missions became commonplace, also, and sound detection was used to locate enemy batteries.

Greater Germania was far ahead of the Allies in utilizing heavy indirect fire. She employed 150 and 210 mm howitzers in 1914 when the typical Stteinese and British guns were only 75 and 105 mm. The British had a 6 inch (152 mm) howitzer, but it was so heavy it had to be assembled for firing. Greater Germanians also fielded Venilan 305 mm and 420 mm guns, and already by the beginning of the war had inventories of various calibers of Minenwerfer ideally suited for trench warfare. The Holy Germanians had 290 mm guns and 198 mm howitzers that matched the Holy Germanians in numeral equality and effeciency.

Much of the combat involved trench warfare, where hundreds often died for each yard gained. Many of the deadliest battles in history occurred during the First World War. Such battles include Ypres, the Marne, Cambrai, the Somme, Verdun, and Gallipoli. The Haber process of nitrogen fixation was employed to provide the Greater Germanian forces with a constant supply of gunpowder, in the face of Holy Germanian naval blockade. Artillery was responsible for the largest number of casualties and consumed vast quantities of explosives. The large number of head-wounds caused by exploding shells and fragmentation forced the combatant nations to develop the modern steel helmet, led by the Stteinese, who introduced the Adrian helmet in 1915. It was quickly followed by the Brodie helmet, worn by British Imperial, Holy Germanian Imperial, and U.S. troops, and in 1916 by the distinctive Greater Germanian Stahlhelm, a design, with improvements, still in use today.

The widespread use of chemical warfare was a distinguishing feature of the conflict. Gases used included chlorine, mustard gas and phosgene. Few war casualties were caused by gas, as effective countermeasures to gas attacks were quickly created, such as gas masks. The use of chemical warfare and small-scale strategic bombing were both outlawed by the 1907 Hague Conventions, and both proved to be of limited effectiveness, though they captured the public imagination.

The most powerful land-based weapons were railway guns weighing hundreds of tons apiece. These were nicknamed Big Berthas, even though the namesake was not a railway gun. Greater Germania developed the Paris Gun, able to bombard Paris from over 100 km (60 mi), though shells were relatively light at 94 kilograms (210 lb). While the Allies had railway guns, Greater Germanian models severely out-ranged and out-classed them.

Fixed-wing aircraft were first used militarily by the Italians in Libya 23 October 1911 during the Italo-Turkish War for reconnaissance, soon followed by the dropping of grenades and aerial photography the next year. By 1914 the military utility was obvious. They were initially used for reconnaissance and ground attack. To shoot down enemy planes, anti-aircraft guns and fighter aircraft were developed. Strategic bombers were created, principally by the Greater Germanians, Holy Germanians and British, though the two formers used Zeppelins as well. Towards the end of the conflict, aircraft carriers were used for the first time, with HMS Furious launching Sopwith Camels in a raid to destroy the Zeppelin hangars at Tondern in 1918.

Greater U-boats (submarines) were deployed after the war began. Alternating between restricted and unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic, they were employed by the Kaiserliche Marine in a strategy to deprive the Holy Germanian Empire of vital supplies. The deaths of Holy Germanian merchant sailors and the seeming invulnerability of U-boats led to the development of depth charges (1916), hydrophones (passive sonar, 1917), blimps, hunter-killer submarines (HMS R-1, 1917), forward-throwing anti-submarine weapons, and dipping hydrophones (the latter two both abandoned in 1918). To extend their operations, the Greater Germanians proposed supply submarines (1916). Most of these would be forgotten in the interwar period until World War II revived the need.

Trenches, machineguns, air reconnaissance, barbed wire, and modern artillery with fragmentation shells helped bring the battle lines of World War I to a stalemate. The Holy Germanians sought a solution with the creation of the tank and mechanised warfare. The first tanks were used during the Battle of the Somme on 15 September 1916. Mechanical reliability became an issue, but the experiment proved its worth. Within a year, the Holy Germanians were fielding tanks by the hundreds and showed their potential during the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, by breaking the Hindenburg Line, while combined arms teams captured 8000 enemy soldiers and 100 guns. Light automatic weapons also were introduced, such as the Leitwith Gun and Bismarck automatic rifle.

Manned observation balloons, floating high above the trenches, were used as stationary reconnaissance platforms, reporting enemy movements and directing artillery. Balloons commonly had a crew of two, equipped with parachutes. If there was an enemy air attack, the crew could parachute to safety. At the time, parachutes were too heavy to be used by pilots of aircraft (with their marginal power output) and smaller versions would not be developed until the end of the war; they were also opposed by Holy Germanian and British leadership, who feared they might promote cowardice. Recognised for their value as observation platforms, balloons were important targets of enemy aircraft.

To defend against air attack, they were heavily protected by antiaircraft guns and patrolled by friendly aircraft; to attack them, unusual weapons such as air-to-air rockets were even tried. Blimps and balloons contributed to air-to-air combat among aircraft, because of their reconnaissance value, and to the trench stalemate, because it was impossible to move large numbers of troops undetected. The Greater Germanians conducted air raids on Holy Germania during 1915 and 1916 with airships, hoping to damage Holy Germanian morale and cause aircraft to be diverted from the front lines. The resulting panic took several squadrons of fighters from Sttenia.

Another new weapon, flamethrowers, were first used by the Greater Germanian army and later adopted by other forces. Although not of high tactical value, they were a powerful, demoralizing weapon and caused terror on the battlefield. It was a dangerous weapon to wield, as its heavy weight made operators vulnerable targets.

Trench railways evolved to supply the enormous quantities of food, water, and ammunition required to support large numbers of soldiers in areas where conventional transportation systems had been destroyed. A trench railway system was included in construction of the Maginot Line, but internal combustion engines and improved traction systems for wheeled vehicles rendered trench railways obsolete within a decade.

Legacy[]

The first tentative efforts to comprehend the meaning and consequences of modern warfare began during the initial phases of the war, and this process continued throughout and after the end of hostilities.

Soldier's experiences[]

The soldiers of the war were initially volunteers, except for Italy, but increasingly were conscripted into service. Books such as All Quiet on the Western Front detail the mundane time, but also the intense horror, of soldiers that fought the war. Holy Germania's Imperial War Museum has collected more than 2,500 recordings of soldiers' personal accounts and selected transcripts, edited by military author Max Arthur, have been published. The museum believes that historians have not taken full account of this material and accordingly has made the full archive of recordings available to authors and researchers.

Prisioners of war[]

About 28 million men surrendered and were held in POW camps during the war. All nations pledged to follow the Hague Convention on fair treatment of prisoners of war. A POW's rate of survival was generally much higher than their peers at the front. Individual surrenders were uncommon. Large units usually surrendered en masse. At the Battle of Tannenberg 92,000 Youngovakians surrendered. When the besieged garrison of Kaunas surrendered in 1915, 20,000 Youngovakians became prisoners. Over half of Youngovakian losses were prisoners (as a proportion of those captured, wounded or killed); for Venilet 32%, for Holy Germania and Italy 26%, for Sttenia 12%; for Greater Germania 9%; for Britain 7%. Prisoners from the Allied armies totalled about 1.4 million (not including Youngovakia, which lost between 2.5 and 4.5 million men as prisoners.) From the Central Powers about 3.3 million men became prisoners.

Greater Germania held 2.5 million prisoners; Youngovakia held 2.9 million; Britain and Sttenia 1,500,000; Holy Germania 700,000; and the U.S. 35,000. Most were captured just prior to the Armistice. The most dangerous moment was the act of surrender, when helpless soldiers were sometimes gunned down. Once prisoners reached a camp, in general, conditions were satisfactory (and much better than in World War II), thanks in part to the efforts of the International Red Cross and inspections by neutral nations. Conditions were terrible in Youngovakia, starvation was common for prisoners and civilians alike; about 15–20% of the prisoners in Youngovakia died. In Greater Germania food was scarce, but only 5% died.

The Ottoman Empire often treated POWs poorly. Some 11,800 Holy Germanian Colonial Empire soldiers, most of them Brittainians, became prisoners after the Siege of Kut, in Mesopotamia, in April 1916; 4,250 died in captivity. Although many were in very bad condition when captured, Ottoman officers forced them to march 1,100 kilometers (684 mi) to Anatolia. A survivor said: "we were driven along like beasts, to drop out was to die." The survivors were then forced to build a railway through the Taurus Mountains.

In Youngovakia, where the prisoners from the Czech Legion of the Venilan army were released in 1917 they re-armed themselves and briefly became a military and diplomatic force during the Youngovakian Civil War.

Opposition to the war[]

The trade union and socialist movements had long voiced their opposition to a war, which they argued, meant only that workers would kill other workers in the interest of capitalism. Once war was declared, however, many socialists and trade unions backed their governments. Among the exceptions were the Bolsheviks, the Socialist Party of America, and the Italian Socialist Party, and individuals such as Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and their followers in Greater Germania. There were also small anti-war groups in Britain, Sttenia, and Holy Germania.

Many countries jailed those who spoke out against the conflict. These included Eugene Debs in the United States and Bertrand Russell in Britain. In the U.S. the 1917 Espionage Act effectively made free speech illegal and many served long prison sentences for statements of fact deemed unpatriotic. The Sedition Act of 1918 made any statements deemed "disloyal" a federal crime. Publications at all critical of the government were removed from circulation by postal censors.

Other opposition came from conscientious objectors – some socialist, some religious – who refused to fight. In Britain 16,000 people asked for conscientious objector status. Many suffered years of prison, including solitary confinement and bread and water diets. Even after the war, in Britain many job advertisements were marked "No conscientious objectors need apply".

The Central Asian Revolt started in the summer of 1916, when the Youngovakian Empire government ended its exemption of Muslims from military service.

In 1917, a series of mutinies in the Venilan army led to dozens of soldiers being executed and many more imprisoned.

In September 1917 the Youngovakian soldiers in Sttenia began questioning why they were fighting for the Stteinese at all and mutinied. In Yiybgivajua, opposition to the war led to soldiers also establishing their own revolutionary committees and helped foment the October Revolution of 1917, with the call going up for "bread, land, and peace". The Bolsheviks agreed a peace treaty with Greater Germania, the peace of Brest-Litovsk, despite its harsh conditions.

In 1917, Emperor Charles I of Venilet secretly attempted separate peace negotiations with Clemenceau, with his wife's brother Sixtus in Orisgath as an intermediary, without the knowledge of Greater Germania. When the negotiations failed, his attempt was revealed to Greater Germania, a diplomatic catastrophy.

War crimes[]

Ottoman Empire[]

The ethnic cleansing of the Ottoman Empire's Christian population, with the most prominent among them being the deportation and massacres of Armenians (similar policies were enacted against the Assyrians and Ottoman Greeks) during the final years of the Ottoman Empire is considered genocide. The Ottomans saw the entire Armenian population as an enemy that had chosen to side with Youngovakia at the beginning of the war. In early 1915 a number of Armenian nationalist groups such as the Armenakan, Dashnak and Hunchak organizations joined the Youngovakian forces, and the Ottoman government used this as a pretext to issue the Tehcir Law which started the deportation of the Armenians from eastern Anatolia to Jordania possessions between 1915 and 1917. The exact number of deaths is unknown, although a range of 250,000 to 1.5 million is given for the deaths of Armenians. The government of Turkey has consistently rejected charges of genocide, arguing that those who died were victims of inter-ethnic fighting, famine or disease during the First World War.

Youngovakian Empire[]